More Than a Historic Home

By Katie Shands

They say old homes tell stories.

From cannonball scars in an antebellum floor to names etched in a wavy glass window, the details in historic houses connect us with the past in a tactile way that textbooks and roped-off museum exhibits just can’t provide. When we walk the rooms of these old places, we’re connected to a larger story. In the words of the late Williamson County historian Virginia Bowman, “It’s impossible to separate the old homes from the lives of those who built and occupied them.” It’s in that vein we share the story of Beechwood Hall and the people, both free and enslaved, who called it home.

Our tale begins with a wedding gift in 1849. When Henry George Washington Mayberry married his second wife, Sophronia Hunter, her parents gave them a farm that was part of the larger family property. This fertile land was located along what is now Bear Creek Road in Leiper’s Fork.

H.G.W. already had a son, Edward, from his first marriage, but it wasn’t long before he and Sophronia began to grow their family. They became parents to Adelia (sadly, she died as an infant), Leonora, and Henry Mayberry. Henry would go on to become president of the Nashville Interurban Railway. This first electric commuter train system connected the big city to Franklin and later, Gallatin. He was also instrumental in creating Franklin’s first spring system.

BUILDING A FAMILY HOME

H.G.W. and Sophronia began their married life in a large log house on their farm. They named it “Liberty Hall” in honor of the Mayberrys’ hometown of Liberty, Virginia. When this house burned in 1851, the couple decided it was time for an upgrade. For their new homesite, the Mayberrys selected a hill in the middle of a sixty-acre, shade-dappled beech grove on their property. They hired the Lillie brothers as their contractors. These men were master architects who designed a number of other fine homes in this county, including Old Town on the Old Natchez Trace and Grassland on Hillsboro Road.

Beechwood Hall was completed circa 1856, using the labor of enslaved persons and materials sourced from the surrounding land. Not only was the home solid with six-inch-thick floors and fourteen-inch walls, it was a showplace. The two-story, brick house boasted a grand entrance hall, high-ceilinged rooms, and handcrafted millwork.

The crowning feature, however, was the winding staircase that greeted visitors in the entryway. An ornately carved newel post anchored the black walnut steps that would be the centerpiece of many weddings, social events, and, much later, country music videos. The staircase was an engineering marvel with no visible support beneath it, and for years to come, architects visited the home to inspect the gravity-defying design.

REMEMBERING THE ENSLAVED PEOPLE

The Mayberry’s plantation eventually grew to become one of the largest in the county. In 1860, they owned more than 1,000 acres and at least forty-two enslaved people who lived in eight cabins on the property.

Though not many records exist to aid in telling the stories of those in bondage, we do know a bit about a man named Carey Mayberry, thanks to the excellent research of historian Tina Cahalan Jones.

Carey was enslaved by the Mayberrys, but after his emancipation, he married Louvenia Marshall (previously owned by Judge John Marshall in Franklin), in 1865. They started their family in a house near Beechwood Hall. Louvenia came into the marriage with a daughter, Emmaline, and the couple went on to have thirteen more children: Louisa, John, William, Columbus, Edith, Eddie, Thomas, Charlie, Frank, Annie, Genevieve, Carey, Jr., and Hattie May.

Despite such humble beginnings, many of their children and grandchildren grew up to be accomplished individuals. Their daughter Annie became a nurse. Grandson John Carnegie Mayberry served in the U.S. Army during World War I and later opened a dental practice in New Jersey. Great-granddaughter Marjorie Mayberry was an aviation cadet and member of the famous Women’s Army Corps.

But perhaps the most poignant achievement in the family belongs to Janet Patton, the great-great-great-granddaughter of Carey and Louvenia. In 1962, nearly 100 years after the Mayberrys were emancipated, Janet was one of two first graders who desegregated Franklin Elementary School. What a fitting way to continue her ancestors’ legacy of strength and fortitude.

Henry George Washington Mayberry

Henry Hunter Mayberry family

Louise Bailey (married name Nunnelly), daughter of Robert A. Bailey, Sr. and Leonora Mayberry Bailey) in front of Beechwood

THE CIVIL WAR COMES TO BEECHWOOD HALL’S DOORSTEP

In the early years, Beechwood Hall was the site of many lavish parties. The Mayberrys would open the folding doors between the rooms on both sides of the spacious hall, creating a dance floor for their guests. In the glow of ceiling lamps, a live band would play popular songs like “The Virginia Reel’’ as hoop-skirted ladies twirled with men in frock coats.

The home also hosted its share of uninvited guests. During the Civil War, H.G.W. Mayberry was stationed in Atlanta as a Confederate captain, leaving Sophronia, the children, and a house servant alone at Beechwood Hall. On several occasions in H.G.W.’s absence, Union soldiers plundered the home. During the lootings, an armed guard would confine everyone to a locked room while troops carried off silver, furnishings and food. Federals also burned the Mayberrys’ gin house, destroying $60,000 worth of cotton.

One night, a soldier fired through the front door, searching for a relative of the Mayberrys believed to be in hiding. When Sophronia told him no one was upstairs, the man fired into the library ceiling to be sure she was being truthful. The hole remained there well into the twentieth century.

Beechwood Hall also served as a makeshift hospital after the bloody Battle of Franklin in 1864. Sophronia took in a number of wounded men whom she often had to spirit away whenever Union troops returned to the house.

As with most plantation owners, H.G.W. incurred a considerable amount of debt due to the war. To avoid losing Beechwood Hall to the bank, he sold it to his son-in-law, Robert A. Bailey, Sr. Robert was married to the Mayberrys’ daughter, Leonora, and they raised five children at Beechwood Hall: Henry, William, Robert, Leonora and Louise. Their daughter Leonora was quite the socialite and even received a personal invitation to the Roosevelt White House when she was only eighteen years old.

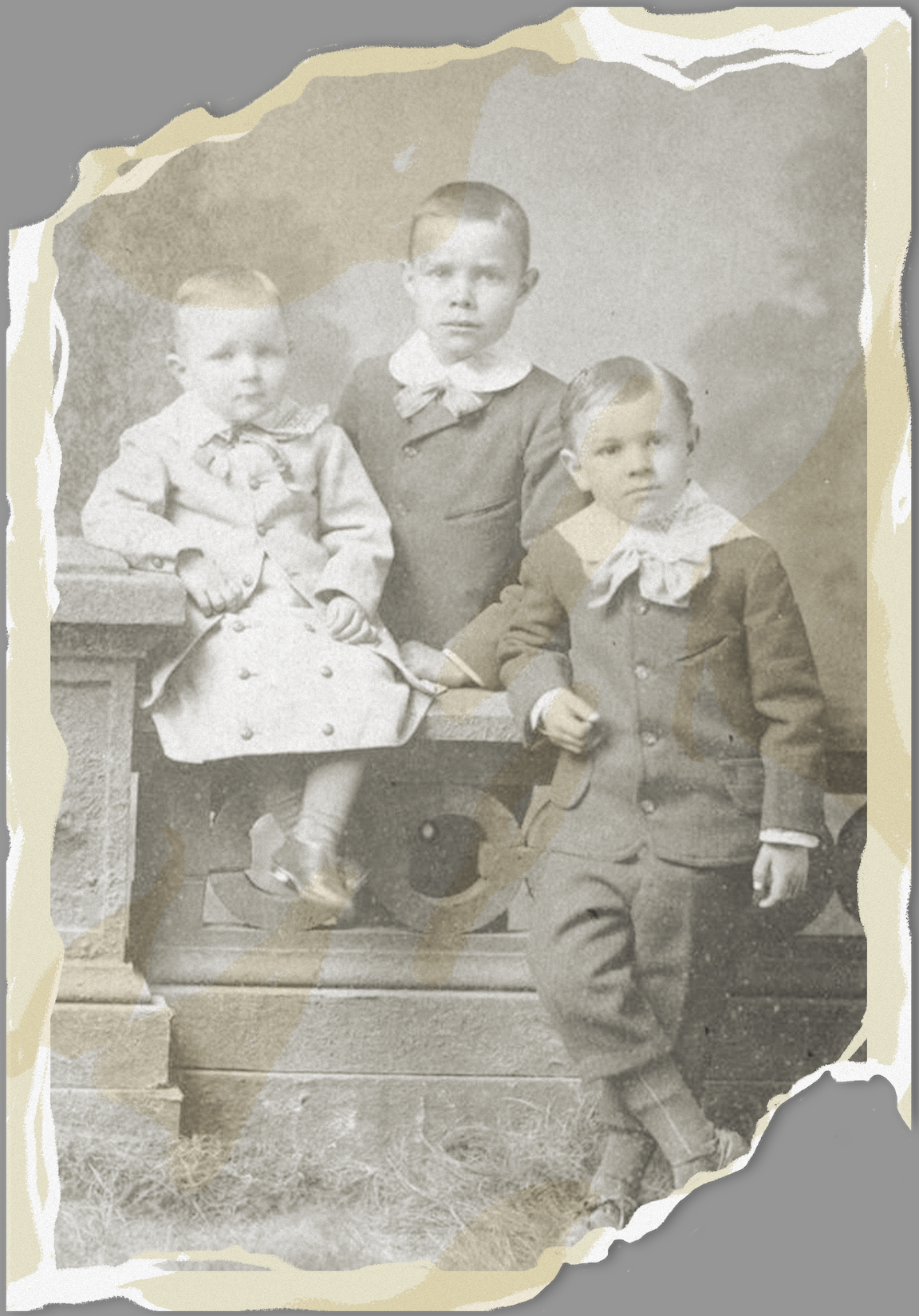

Henry Mayberry Bailey, William Thomas Bailey, Robert Albert Bailey, Jr. (sons of Robert Albert Bailey, Sr. and Leonora Mayberry Bailey)

Louise Bailey Nunnelly (daughter of Robert A. Bailey, Sr. and Leonora Mayberry Bailey) at Beechwood

FROM A COUNTRY MUSIC STAR’S HOUSE TO A DUSTY BARN

After Robert and Leonora died, the Bailey heirs auctioned off Beechwood Hall. It passed through a string of owners, including country music legend Hank Williams, Sr., in 1951. However, he never actually lived in the house. After some personal setbacks, Hank sold it the following year at a loss.

As time marched on, the old mansion deteriorated until it was re-purposed into a barn. Instead of blushing brides, the staircase held bales of hay. A farm truck dripped oil onto the floor in the entrance hall where finely dressed couples once danced. Long-gone were the elegant furnishings; lumber and machinery now filled the rooms. Just when all hope seemed lost, Harry and Betty Morel purchased Beechwood Hall and undertook a massive renovation in the late sixties. Despite the neglect, the house’s bones remained solid thanks to the excellence of the original building materials. The Morels gave the home a second life, and it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

Tim McGraw and Faith Hill later purchased Beechwood Hall, but never actually lived there. In 2021, they sold the property to the investor group BKDM who, in turn, sold it to local businessman Larry Keele.

AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Beechwood Hall has survived war, economic busts, abuse and the ravages of mother nature, but this may be its final hour. The home sat empty for years before Keele’s ownership, and after making the purchase, he hired a structural engineer who deemed it dangerous. Plans were drawn up for a new home to be built in place of Beechwood Hall. A rear addition from the 1970s was demolished, and the staircase’s banister and newel post were removed and placed in storage for safekeeping. However, the architect has since walked away from the project, saying he couldn’t be a part of tearing down the house.

Present Day Beechwood Hall

The Heritage Foundation of Williamson County has announced they are exploring preservation solutions with Keele and securing the home for winter. Though Keele has given no formal guarantee the house won’t eventually see the wrecking ball, he says he’s happily working with the Foundation and looking “at all potential options for the property.”

A grassroots effort is also underway to save Beechwood Hall. Preservationist Mary Pearce, Mike Wolfe of American Pickers fame, and LovelyFranklin.com co-founder Buffie Baril, are among those leading the charge. One of their main focuses is establishing a historic overlay for the county. Contrary to popular belief, inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places doesn’t protect a property from destruction. Only a historic overlay would provide such a safeguard, which the unincorporated part of Williamson County doesn’t currently have. This type of zoning would require owners to obtain a demolition permit and undergo a 120-day waiting period before destroying a historic property. The group has started a petition to advocate for an overlay and to ask for a commitment from Keele to help preserve the home.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

Historic preservation is about more than salvaging a structure. It’s about preserving the memory of the people who lived and worked there. It’s about connecting to and learning from our collective past. It’s about keeping the unique features that prevent a community from becoming cookie-cutter.

May this situation with Beechwood Hall be a cautionary tale to us all about the importance of caring for these properties. Indeed, old houses tell stories, and with each one that is lost, we rip out another page from Williamson County’s past. The future is yet unwritten for Beechwood Hall, but we sincerely hope it’s not the final chapter for this old house. For more information on efforts to preserve historic Beechwood go to williamsonheritage.org and SaveBeechwood.org.